I will be doing a set of posts on some really delicious wines from Spain that you might not be familiar with. The two wines that Spain is best known for are the red wines from the La Rioja region and the Cava sparkling wines from the Priorat region outside of Barcelona. Both are excellent but there are eight other Spanish wines that we really enjoy, many of which we learned about on our great wine tasting trip to Spain last September. Here is a link to a write up on that trip – https://billwinetravelfood.com/2022/10/10/two-week-spanish-wine-tasting-trip/. This years trip was recently announced. If you want a link to the information for this year’s Spanish Wine Tasting trip, let me know in Comments where to send it. I highly recommend it.

The first wine that I will be covering is Albariño from the Rias Baixas DO. It is a crisp dry white wine that is our favorite wine for seafood and generally sells for under $20. The picture is of a roadside stand in Spain with a whole selection of Albariños, most of them were about €8 and these are only sold locally. If you go into a Spanish bar or restaurant and ask for glass of Albariño, it usually costs about €2. There is a pretty good availability of a number of Albariños in the US.

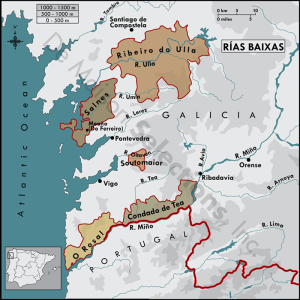

For those of you whose Spanish is as bad as mine, the squiggle over the n in Albariño adds a y sound to the pronunciation – al bar EEN yo. The x is Rias Baixas has a sh sound so the region is pronounced – re az BY chees. It is believed that the Albariño grape was introduced to the area in the 12th century by the Cistercian monks of the Monastery of Armenteira. The map shows the Rias Baixas region which is in northwestern Spain, right on the Atlantic and just across the border from Portugal. That same grape is called Alvarinho in the Portuguese province of Portugal, just south or Rias Baixas and I am a big fan of the Portuguese version of this wine as well.

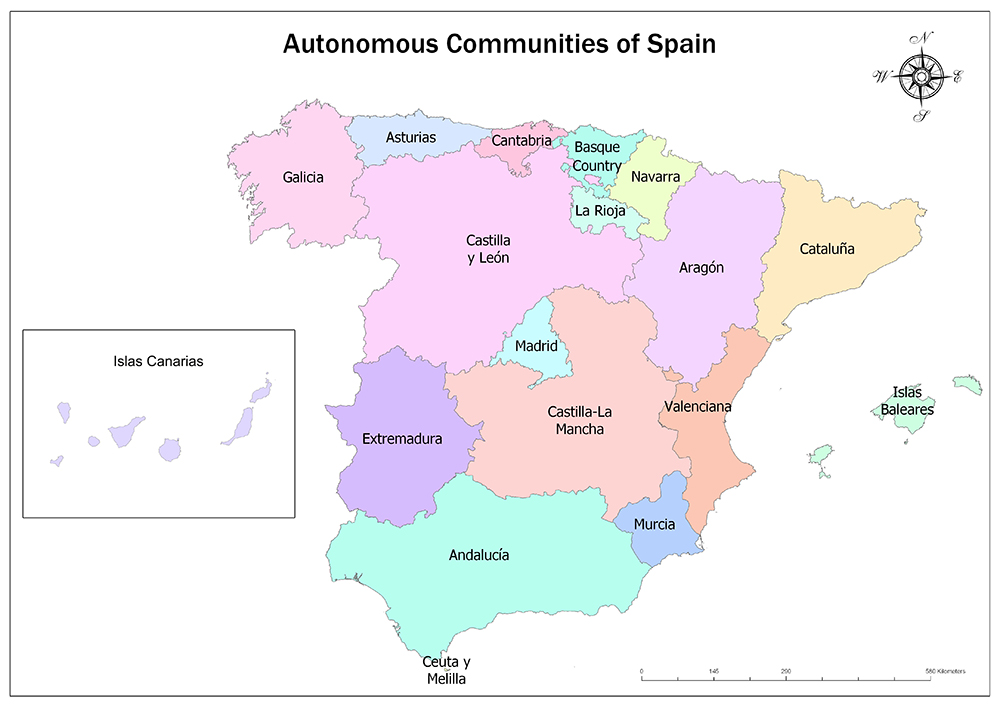

In my write up of these other eight wines I will consistently recommend that you get ones that have the DO designation on the label. This “Denominación de Origen” (designation of origin) lets you know that the wine you are considering met a set of standards defined by the leading vineyards in a specific geographic area and therefore is likely of good quality. It may not be to your taste, and any bottle can have a bad cork or have been exposed to too high or too low temperatures in transit into this country – so there are no guarantees. But wines that do not have a DO have not committed to those standards of quality and therefore are a much higher risk. Spain is divided into 17 Autonomous Communities (AC), which are wine making regions, and they are shown in the map below, which can also be downloaded. In each of those AC’s, wine makers in some of the smaller geographic have banded together and defined a set of standards that a wine must meet in order to put DO on the label, e.g., DO Rias Baixas in the Galicia AC. Each DO has a group of members that monitors compliance with those rules and determines who can put that designation on their label. There are approximately 70 DO’s in Spain.

The Spanish claim that when God finished creating the world he looked down and was very proud of his work. He reached out to touch it and his thumb and four fingers made the inlets of Rias Baixas. The Albariño vineyards are right on the ocean and even if God did not touch this area with his hand, he put those grapes on the earth to accompany seafood. You can almost smell the salt air when you breath in the aroma of Albariño. The climate is very humid with warm summers influenced by the Gulf Stream.

In addition to making delicious wine that is mostly under $20 in the US and half that cost in Spain, the region also is a major producer of shellfish. The first picture shows some of the over 2,200 of barges or “Bateas” in one of the inlets, the Ria de Arousa , where they raise enormous amounts of shellfish. Each of these bateas has 420 ropes hanging down 5-10 meters into the water. Each rope can be used to raise mussels, scallops, or oysters. The second picture shows one of the crew members on the bateas with a rope for each kind of shellfish. Each is seeded with tiny baby shells and put down in the Ria which is very rich is the ocean plant life that the shellfish thrive on. The rope with the mussels can grow about 20 kilos of mussels on each meter of rope in two years and there are about 300 mussels in the picture below. The scallop and oyster ropes each grow a few dozen full sized shellfish in 3 years. Because of the 2-3 year time required, thousands of bateas are needed so a significant crop can be harvested each year.

Our house Albariño is La Caña (CAHN ya) which is owned and operated by Jorge Ordoñez. It consistently gets 90-92 points from the reviewers and is about $18-20 and pretty widely available in the US. It demonstrates the complexity, intensity, and longevity Albariño can achieve when sourced from old vineyards and using serious winemaking practices. They ferment 35% of the wines in small old oak puncheons and 65% in stainless steel tanks. The pressed grapes are left for Sur le aging for eight months and are punched down biweekly.

Martin Codax is also very widely available in the US. This is a Co-op wine with grapes purchased from a number of different vineyards. It is a very nice table wine that retails for about $15,but just a little below the La Caña in quality in my opinion.

Quinta de Couselo has pretty good distribution in the US and offers three Albariños. Their Barbuntin is a lighter wine made from younger vines, generally less than 30 years old. It sells in the $12-15 range. I like the richer Albariños and would take either the Martin Codax or the La Caña over this one. Their Rosal is in the $20 price range, and I found it delightful. Their Turonia is the best of the Couselo Albariños and fully worth the $24 price that on line retailers in the US have it for and I have a couple of bottles in my cellar.

I open my Albariños three to four hours before drinking them and leave them open in the refrigerator to breathe. I take them out of the refrigerator at least 30 minutes before pouring the wine to get the temperature up to the high fifties Fahrenheit. Another theme you will see in my posts on wine is that we don’t let our wines breathe and open up, we drink our white wines much too cold, and our red wines too warm.